Why the Minimum Viable Product Is Dead

Okay, okay, maybe it’s not dead, but the way we treat MVPs today is NOT how they were originally intended, and that’s costing companies their ability to build truly customer-centric products that actually impact business metrics.

The good news is that there’s a different, more impactful way of thinking about early releases, but before we talk about the alternative, let’s first address how we got here.

Where did we go wrong with the MVP?

The original intention of the MVP was brilliant. It allowed companies to put into the market the least amount of value/functionality the customer would find helpful so that teams could launch sooner, learn faster, and refine based on real feedback.

But, as often happens when enterprise gets a hold of innovative approaches to value delivery, the term morphed into a faint shadow of its original intent. This is why we can’t have nice things: we ruin good ideas by trying to make them work at scale!

What was once a nimble, scrappy concept has now become an exercise in launching the least amount of functionality that a company feels comfortable attaching their name to. Today, we can see a gulf between a true MVP and a nearly fully-finished product.

Essentially, the MVP has become an overstuffed chair. This is dangerous because products/features are now so packed with variables that it’s increasingly difficult for teams to learn what’s working for their users and what isn’t. And if a product isn’t making someone’s life better, it isn’t doing its job.

We’ve seriously departed from the original notion of creating a small chunk of value and learning from it, but there’s hope.

What’s the alternative?

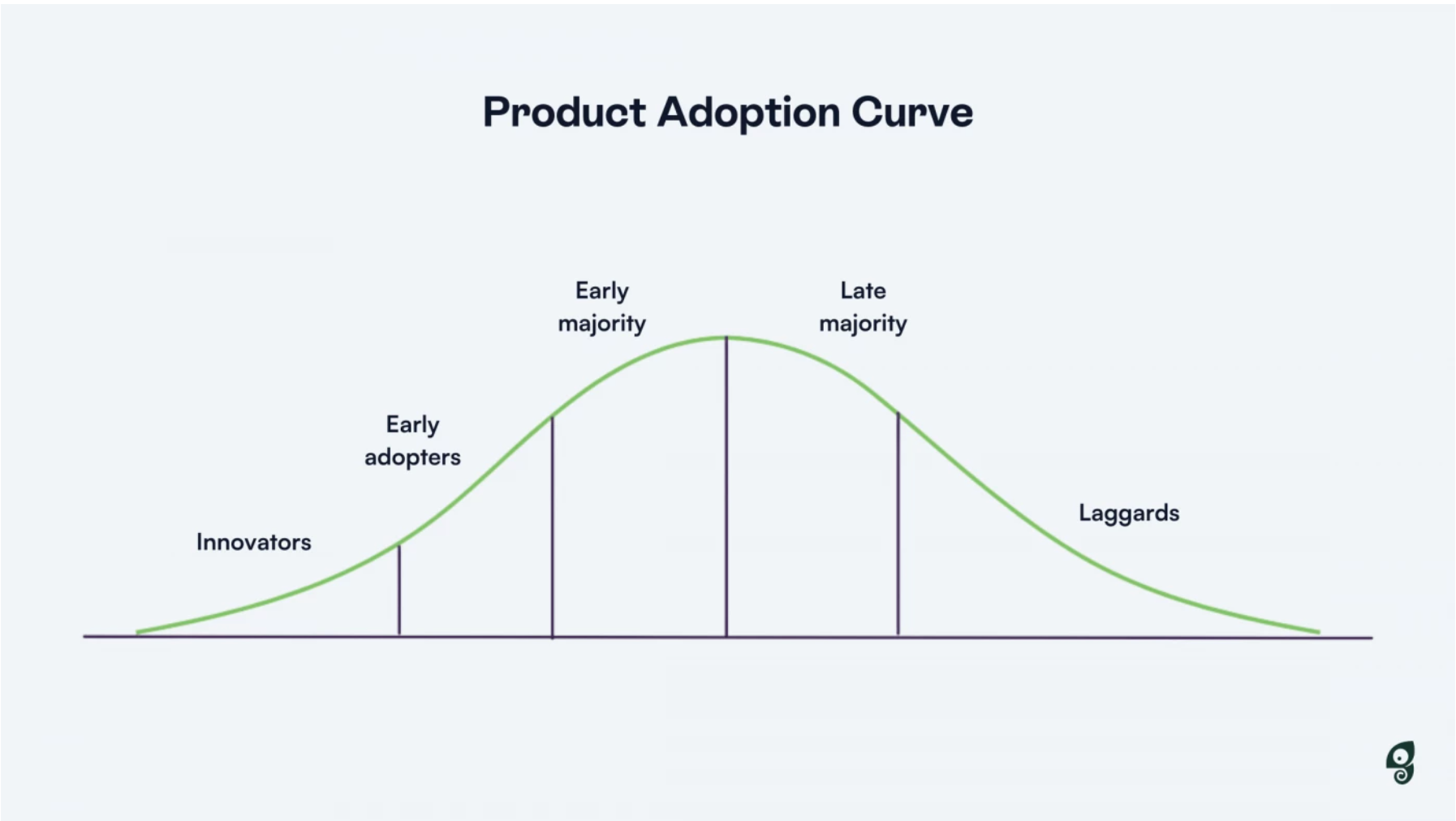

Instead of thinking about MVP – which has become a very technology-first approach rather than a people-first approach – we should think about an Adoption Curve, both in terms of how we think about which customers will want to try new things, and when they’re likely to want to do it.

This concept places functionality on a curve that correlates with different customer segments: Innovators, Early Adopters, Early Majority, Late Majority, Laggards.

Image source: Chameleon Intelligent Tech, Inc.

On one end of the curve you have your Innovators: a group of people who love your product and your company, and being part of new releases. They get a surge of excitement when they see the word “BETA” and want to test new features and functions, and help you work out the kinks along the way. They’re also the most forgiving – they’re not looking for perfection, they’re looking to be treated like an insider – which is why you let them in early.

Once you have feedback from your Innovators, teams can improve and smooth the experience while increasing functionality and participation with Early Adopters and, subsequently, the Early Majority.

Late Majority and Laggards are always going to be the people who don’t like change (even if the experience is better), so it makes sense that they would be the final groups to engage with the new product or feature set only after most of the kinks are worked out.

Here’s why this is brilliant: it allows product teams to get back to the original idea of the MVP by honing in on the right customer segments to test and learn from rather than waiting to engage the majority of users with something that’s almost done (that’s not an MVP, that’s a scaled product).

Why it works

By embracing the Adoption Curve, product teams can shift the intended idea of the MVP back to its scrappy nature while also minimizing perfectionistic tendencies since you have the security of engaging your Innovator segment as your guinea pigs.

More importantly, it helps teams avoid stuffing too much into a release – and taking too long to release – then struggling to learn what’s working and what’s not.

Now, if you aren’t sure who your Innovators are, that’s another issue. My quick advice? Pause and do some customer-centric research so you can categorize your users before building features.

Sometimes the most helpful exercise is a process of elimination: start by giving shape to the opposing ends of the curve – your Innovators and your Laggards.

The former are the users that always sign up for something first, are willing to pay for a service when others aren’t, and have the highest engagement with your product. The Laggards are the folks who always grumble at change, are the last to sign up for something, and cling to an old system/platform until they’re forced off it.

So, is the MVP really dead?

Well, no, of course not. But the way the idea has evolved and is being used in today's business context is totally divorced from the original intention. As a result, most MVPs are missing the mark.

It’s necessary to reposition how we think about MVP and where it comes into play, otherwise teams risk losing precious time and insights, and the ability to build something that’s a truly irreplaceable benefit to their users.